Commanding change: What can we learn from the Swedish Armed Forces’ leadership program on gender equality?

Posted Wednesday, 10 Dec 2025 by Louise Olsson &

2026 will be the “Total defence” year in Norway.

What can we learn from senior military leaders about how to more effectively consider gender equality issues when creating conditions for sustainable organizational development? Drawing on unique insights from an organization-wide leadership training program within the Swedish Armed Forces, this commentary addresses that question.

Understanding the many roles gender equality can serve in organizational capacity building and human resource management is critical, yet complex. Most military organizations struggle to include gender equality issues as integrated parts of regular organizational decisions and processes.

The inability to fully consider gender equality issues creates vulnerabilities, as this prevents us from effectively addressing serious problems such as reduced unit cohesion, lower retention levels of personnel, and limited situational awareness; vulnerabilities which can weaken a military organization. Importantly, the inability to properly address gender equality issues also entails not delivering fully on political decisions and legal requirements of creating equal opportunities for men and women. What the Swedish Armed Forces sees gender equality as: a tool for progress and a goal in its own right.

Still, driving organizational progress that enhances gender equality parameters can be some of the toughest for leaders to undertake, especially in a military context. While there has long been research acknowledging the centrality of leadership for effective organizational development, there is, in fact, very limited knowledge around what military leaders themselves view as the best ways forward. Learning from leaders is central to forming more effective future strategies for capacity building that include gender equality issues.

By the end of 2025, the Swedish Armed Forces will have put over 150 of its senior leaders through a training program which focuses on improving the understanding of gender equality in relation to reaching the regular mandate and in making daily decisions to develop the organization. This is one of the most comprehensive leadership training efforts of its kind.

Systematic leadership analyses – in the form of so called action plans – produced by the participants offer us unique opportunities to learn more about leadership-driven change related to gender equality issues. With permission of the participants, this commentary is based on 78 such in-depth analyses by mid-level leaders, combined with observations from one of the authors who served as a coach and lecturer within the training program. We use this material to offer initial reflections on our research into how stronger pathways for leadership-driven progress within military organizations can be shaped.

The Senior Leadership Program (JHC)

In 2019, the strategic leadership of the Swedish Armed Forces decided to institutionalize a training program entitled ‘Gender Mainstreaming for Senior Leaders’ (‘Jämställdhetsintegrering för högre chefer’, in Swedish – henceforth JHC). Earlier iterations of the program – the then-called ‘Gender Coach program’ ran first in 2007, followed by three subsequent programs in 2013, 2015, and 2019 – which were attended by both former and current Chiefs of Defence. During the 2019 program, the strategic leadership had articulated a need to build knowledge, especially among mid-level leaders throughout the organization, to create the foundation for change. To that end, the JHC program was instituted.

In 2021, the JHC program was rolled out under the leadership of Course Director Ulrika Eklund, a trainer and expert with decades of experience both nationally and internationally on gender integration for organizational improvements. The program is run by the Management Unit at the Military Academy Karlberg, a Unit that regularly handles internal professional development in the Swedish Armed Forces.

The course was launched at a crucial time. The Swedish Armed Forces was undergoing major and rapid changes overall. There was a national turn in defence – i.e., a need to quickly rebuild national defence capacity and to improve recruitment, including through re-instituting conscription, this time for both men and women – as the security in the Nordic region was deteriorating. This process would be further accelerated by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and Sweden's subsequent decision to join NATO. In addition to the JHC program, several integral components for change related to gender equality – such as gender policy development and the use of gender advisors and experts on preventing harassment – were run in parallel.

The pedagogical approach: Strengthen the connection between knowledge and ability

The program consists of 110 hours stretching over 12 months. This 'stretched out' format has two benefits. First, it enables senior leaders to combine the course with regular work. Second, it allows for using a pedagogical approach that combines three elements – leadership seminars, coaching, and individual analysis formed into an action plan – which jointly can account for some recognized and serious challenges to using training to raise capacity:

- Leadership seminars combine expert presentations and readings with group discussions. These enable the i) forming of joint understandings of strategic decisions and policy, ii) identification of common leadership approaches, and iii) sharing of experiences on how to address concrete issues. Combined, these serve to strengthen a coherent organizational leadership approach across the organization.

Establishing joint understandings and common approaches among leaders in an organization is important. Gender equality issues can be difficult for individual leaders to tackle, given their systemic and complex nature. Promoting joint organizational approaches is furthermore important for overcoming what research has identified as a marginalization of gender; that is, that issues associated with gender equality run in separate, weaker tracks in military organizations, away from regular decision-making processes and leadership responsibilities. Hence, the program seeks to promote a consistent organizational approach which entails adapting established and regular decision-making processes. The focus is on those processes that produce the main outcomes of the organization. - Coaching sessions with experts individually and in groups allow for reflecting, on a confidential basis, on efforts and challenges that appear during a leader’s everyday practices.

The coaching seeks to strengthen the forming of leadership confidence and capacity to practically tackle gender-equality issues in their specific organizational context. The 'coach' role in this program is a combination of coach and expert on gender equality who can provide additional perspectives and ideas for solutions. Having an external coach enables open discussions without risking to negatively affect regular processes or decision-making hierarchies. - Structured individual analysis formed into an action plan supports the leader’s ability to systematically identify and address gender equality issues. As part of the analysis, the leaders each select one specific gender equality issue that they think is important to change. Then they formulate an action plan outlining how they think they can address that issue through their daily work. In a manner of speaking, this is a gender analysis adapted to the leadership level.

The task to form an action plan is something participants work on throughout the 12-month period with regular input from their coach and their peers. Practically, this means that the course provides participants with an analytical structure which supports their forming of a more detailed understanding of existing problems and what it can involve to move from problem identification to action on a specific gender equality issue. Through this task, the JHC Program seeks to move participants beyond a core challenge commonly associated with training on gender – that it remains too abstract (theoretical) and too generic (disconnected from a specific organizational context) – by allowing participants over time to develop a systematic understanding set in the context of their organization’s overall mission as well as their specific leadership responsibilities.

It is the unique material from the leaders’ action plans that we draw on for our project, with the participants’ permission.

What can we learn from the JHC leadership analyses?

The largest part of the JHC program courses have targeted leaders at the OF5 level; that is, the equivalent of colonels/commanders and their civilian peers. This is the mid-level leader group in focus for this commentary. The absolute majority of OF5 leaders participating in the program have been male military officers, and most have either led a section at the Armed Forces’ HQ or headed a more independent organizational unit, such as a regiment, school, or centre.

When we study leaders’ potential to influence sustainable change around gender equality, we argue that we must consider the heterogeneity of the leadership group. This takes several forms in our material:

- What specific leadership responsibilities participants have within the organization - what we call their ‘functional responsibilities’ – varies substantially. For example, heading a regiment or being in charge of a section on military planning provides very different entry-points for processing the course content and connecting it to their everyday tasks.

- What specific gender equality issues that need to be considered vary substantially according to functional responsibilities. For example, being in charge of acquiring equipment involves very different gender equality issues than if you are responsible for long-term operational planning. The form of unit you lead also matters for the size of the problems you can face. For example, if you run a regiment or school, you are responsible for the overall working environment on an aggregate level, compared to being responsible for such matters in a smaller unit at HQ.

- What forms of processes and resources leaders control can directly affect outcomes on gender equality. For instance, the head of a regiment could have more control over resources and outcomes in his/her organizational unit than a leader that contributes one part in a larger policy or planning process at HQ, a process involving several other unit contributions to the aggregated outcome. If these efforts are coordinated, however, then leaders operating around the same HQ processes could potentially produce larger outcomes. Leaders of independent units, such as regiments, could also be overwhelmed by the sheer number of different gender equality issues under their responsibility.

Interestingly, as the program has progressed between 2021-2025, the OF5 leaders appear to have expanded from what we call a basic ‘professional responsibilities’ understanding (i.e., that everyone in the Swedish Armed Forces is responsible for gender equality progress), to one that we label a ‘functional responsibilities’ understanding. That is, there appears to be a rising awareness among the leaders themselves that a) they should focus on the gender equality issues that fall directly under their specific functional responsibilities, and that b) they are responsible for driving and following up progress on these issues as part of their regular job.

While that would seem obvious, earlier programs displayed a higher degree of mid-level leaders, instead of either remaining too generic or attempting to align their action plans to the organization’s overarching strategic objectives. For example, a leader could choose to focus their plan on increasing the number of women in the Swedish Armed Forces, as they knew that this was a strategic priority set by the Chief of Defence – even in instances when recruitment was not an issue that this individual leader could directly affect. As the connection to individual leaders’ functional role has started to become more articulated in the leadership group, also with the assistance of the course leaders and coaches, this tendency has decreased over time.[1]

This points, however, to a more potential fundamental weakness in the starting point of some efforts to improve gender equality – vague parameters set around unclear objectives. To understand that problem more in-depth, we need to look closer at how leaders approach change.

What do leaders want to change? Moving from the aggregated generic to the granularly concrete

To ensure relevance, the JHC program in the 2021-2025 period formed its content around the policies on gender equality that the Swedish Armed Forces had adopted. These policies outlined problem areas that had been identified as central for the Swedish Armed Forces to address, as well as outlined gender integration as the main method to handle them. In this period, the policies had a focus on four areas, as outlined in Figure 1. i) Integration into regular processes (method), ii) Equal opportunities, iii) Increase the number of women, and iv) Gender in military operations. The last point concerns issues related to Women, Peace and Security, such as women's security, participation, and access to resources, that exist mainly in an area of operations. As visible in Figure 1, the leaders mainly opted to focus their analysis and action plan on efforts to increase the number of women and adapting regular working methods to improve integration. The latter often involves improving the capacity of the organization to address problems related to equal opportunities. A reason for why so few focus on gender in military operations could be that not many leaders have responsibilities that directly involve military planning.

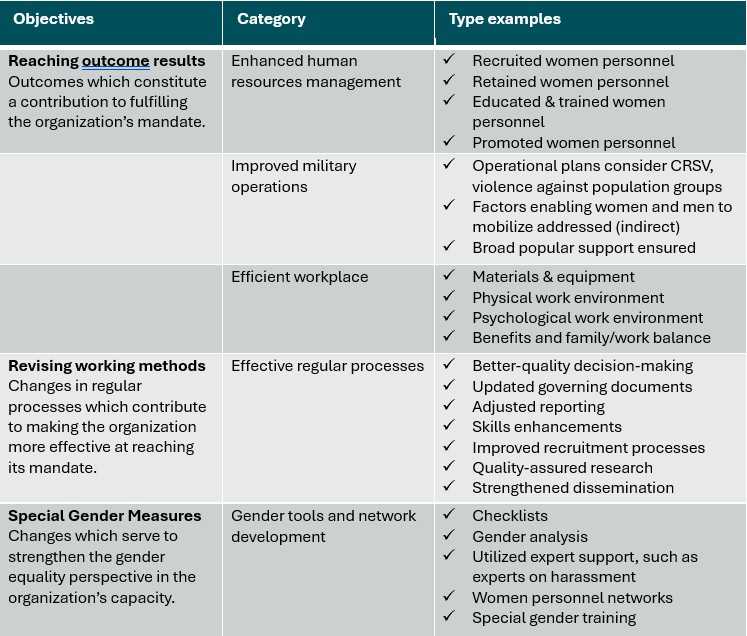

When formulating a plan for change, leaders have to move from these wider and generic gender equality areas to identify a concrete problem to analyse and address within a specific time frame. The effect of this is that they unearth numerous complex and granular issues on gender equality that fall within their functional responsibility, and where it is possible to form a time-specific implementation plan. In Figure 2, we map out some examples of types of issues that the action plans have identified.

As is noticeable, the main starting point for the four wider generic areas is the need to improve certain areas of gender equality per se. That is, they do not necessarily start from the perspective of explicitly connecting and explaining these areas in relation to fulfilling the overarching mandate of the Swedish Armed Forces (i.e., defend Sweden and its allies). This starting point appears to be a challenge for many leaders, potentially as it is the aim and content of the organizational mandate that sets the overarching direction and parameters for a leader's efforts and responsibilities. What is indicated in the material that many of the individual leaders produce, is that they therefore have to undertake a detailed effort of what we here call 'reframing'. That is, they try to identify and place specific gender equality issues within the Swedish Armed Forces’ overarching mandate and organizational needs – such as enhanced human resource management or an efficient workplace. In Figure 2, we have grouped these issues into categories which speak to overarching organizational capacity building and mandate delivery.

Figure 2: Objective, category, and type examples

As a core part of leadership is to guide your employees to fulfil the organizational mandate and needs, the process of reframing gender equality is perhaps less than surprising. However, observing it does point to a potential stumbling block in gender integration. Policies on gender equality request a lot from individual leaders if the policies have not served to effectively and concretely translate and place gender equality issues into the overall aim of an organization to set clearer parameters and coordinate efforts toward prioritized expected outcomes.

Relatedly, what we can also observe is that the categories, in turn, can be grouped under three different forms of objectives that the leaders strive to accomplish. The two most common, as evidenced by the leaders’ action plans, are directly related to fulfilling the mandate and organizational needs. The first are objectives that relate to reaching tangible outcome results, such as improved personnel recruitment or retention, or better equipment for all personnel so that they can perform effectively. The second involves revising working methods, i.e., improved regular methods and processes. Here, the aim is often to be able to handle the same form of gender equality issue consistently over time and space by strengthening the day-to-day decision-making and accountability processes. For example, an action plan could promote that sexual harassment cases should be consistently and effectively integrated, addressed, and followed-up by leaders in the formal forums regularly managing problems concerning the working environment. The plan to make the regular working processes handle harassment more effectively had, as a long-term goal, to produce a tangible outcome – the reduction in the number of harassment cases through clearer accountability mechanisms. Importantly, however, some plans indicate that not all leaders are able to connect a revision of the working methods to such actual tangible outcomes. If this is the case, this gap between method and outcome needs to be addressed, as it could be the reason why gender equality efforts sometimes can become symbolic or only a bureaucratic 'check the box'.

A few leaders also consider the third category – undertaking special gender measures, such as gender training or checklists – in their plans. The reason why these are not so often in focus may be that they are placed further away from regular processes over which the leader normally practices control. This could make them difficult to use directly. There are also some possible risks that should be discussed for when these measures are suggested in change-processes. For instance, women’s professional networks can constitute good consultative forums. However, in a few plans, these are indicated as actors that should drive change. As they have no formal role and cannot directly affect decision-making, this could lead to the risk of marginalization of gender equality issues.

Conclusions

What can we then learn from the participating leaders on how leadership-driven change in military organizations can be reinforced and obstacles to organizational progress overcome?

This commentary has presented some preliminary insights from unique material produced by leaders in the context of the Swedish Armed Forces’ JHC program. This initial analysis allows us to identify several potential practical steps for change and to explore pathways which may guide both efforts to enhance gender equality in military organizations and further research:

- The importance of continuing to concretely clarify functional responsibilities in order to more effectively drive and follow-up change in the areas for which individual leaders are responsible.

- The need to make visible, concretize, and prioritize among the plethora of types of gender equality issues that fall under the military mandate and organization. More specifically, leader insights indicate that parameters of expected change should be made clearer and be related to specific prioritized outcomes. This is related to the third and final pathway.

- Leaders motivate their efforts in the context of the main mandate, objectives, and processes of the Swedish Armed Forces – defend Sweden and its allies. If supporting policies on gender equality instead start from the viewpoint of improving gender equality per se, our results indicate that this could necessitate a costly process of reformulation; a translation even more costly if it has to be undertaken by all leaders individually. A joint organizational reframing, reinforced through regular doctrines and guiding documents, can lessen this cost. The Swedish Armed Forces' new concept paper on gender equality is an important step in that direction.

In short, the leaders’ insights demonstrate that there is no quick fix to the numerous and complex structural challenges identified in research and practice. Their observations also highlight potential pitfalls in our current approaches to gender mainstreaming to explore further. That said, drawing on the participants’ leadership expertise around organizational development also allows us to identify ways in which coordinated leadership efforts could drive systematic change toward concretized objectives. This suggests that training to raise leadership capacity fills one important part in a larger puzzle that needs to be combined with other strategic decisions on consistent and clear organisational outcome objectives and accountability formats. Hence, the Swedish Armed Forces' JHC Program provides important lessons for other military organizations and for further research on gender equality and military organizations.

About the project

Funded by the Forte project Should I stay or should I go? The determinants of retention of female personnel in the Swedish Armed Forces – Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and the Swedish Research Council Project All Aboard!? A multi-level analysis of societal security and preparedness in Sweden and Norway – Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), we have received permission from JHC Course participants to use the analyses in the action plans for research studies. One of us has also acted as a presenter and coach in the program since 2021 (and since 2013 in earlier iterations of the program) which allows for more qualitative first observations about the progress over time.

This commentary is based on the initial analysis of 78 action plans at the OF 5 level. It is the first in a series of publications on gender equality and Women, Peace and Security from these projects related to the ongoing transformation of organizations adapting to the changing global security landscape.

- Louise Olsson is a Research Director/Senior Researcher at PRIO and leads PRIOs Gender Research Group. Her research focuses on the gendered dynamics of war, and gender mainstreaming and Women, Peace and Security in Nordic national security and defence policies and implementation. She is a coach and lecturer in the JHC Program.

- Sara Lindberg Bromley is acting Senior Lecturer/Associate Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, and Research Fellow with the Asia-Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. Sara’s principal areas of research relate to international peace operations, military organisations, political violence, and civil war dynamics. In a forthcoming project, Sara will study societal preparedness and security in the Swedish context.

[1] Interestingly, this has happened in parallel to a process on clarifying functional responsibilities overall in the Swedish Armed Forces.

![Фото: Атлантический совет / Евразийский центр [text for the photo]. Atlantic Council / Eurasia Center](https://cdn.cloud.prio.org/images/2fdc5ace6a3c4e88bc368dba966c2858.jpg?x=900&y=300&m=AutomaticCover&hp=Center&vp=Leading&ho=0&vo=20&)